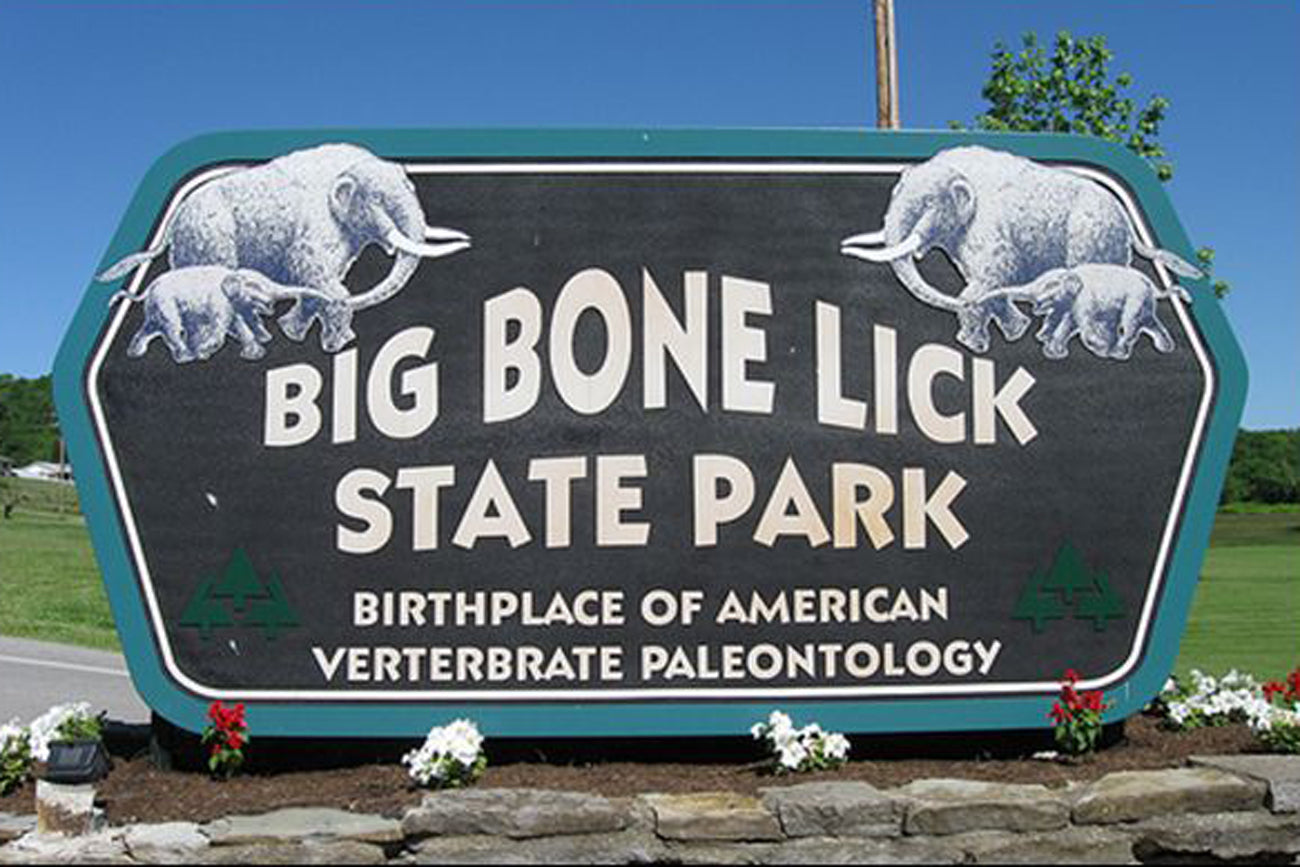

Big Bone Lick contains a treasure trove of prehistoric fossils, yet today doesn't attract much attention beyond its funny name. Here's why it should.

Many years ago I tried to promote Big Bone Lick (the geographical area, not the park per se) as one of the most unique natural scientific areas in the United States. Folks who giggle at the name as they drive down the interstate may not know that Big Bone Lick is the birthplace of North American vertebrate paleontology. Thomas Jefferson, Ben Franklin, all the science gurus of Great Britain, France, Ireland and beyond all paid a visit at one point or another.

I'm talking specifically about the valley that runs through Boone County, Kentucky, and along the Ohio River course — starting at the mouth of Big Bone Creek at Ohio River Mile 516.5, to be exact.

When you think of Kentucky, you don't automatically think of 12,000 years ago, when glacial ice covered both sides of the Ohio Valley. You don't think of the grasses and bushes and shrubs and trees right here that were not encased in a mile or two of solid ice, either. Had you been witness to this scene, you might exclaim, "what in Hades is that mammoth animal coming my way?" And you'd be right. It's a mammoth. And right behind it a group of mastodons. One is grazing on the native grasses, while the other is browsing on the woody shrubs and trees for nourishment to continue their never-ending trek for food and sustenance. And right on their tails is a group of funny-looking little men carrying spears with sharpened rocks on the end and spear launchers, with their immediate family members in tow, all smacking their lips, thinking they're going to be feasting on one of these huge critters for supper!

Overly simplified, sure, but essentially that's the prehistoric story for this part of Kentucky. During the last ice age, our oceans' waters were being used up to form sheets of solid ice, sometimes two-miles thick! This lowered the existing water levels enough to expose a solid land bridge from Asia to North America, called Beringia. We know it today as the Bering Straight. Across this solid land bridge, the nomadic, wandering herds of the Pleistocene megafauna made their way for the very first time onto our continent.

Eventually these huge Pleistocene mammals became extinct. To cut to the chase — humans hunted them to extinction. And the best place to hunt them was where they congregated for their salt intake. There were many, many salt sources, called licks, in the area of their grazing territory. Since these animals were all plant eaters, they had to get their dietary supply of salt by 'licking' the ground near these salty deposits. (By contrast, meat-eaters get their supply from the meat they consumed.) So, they were hunted at these licks and their carcasses rotted away, leaving behind oversized remains, a.k.a. Big Bones.

One-stop shopping

All throughout pre-history, humans knew about Big Bone Lick. It became a one-stop-shopping-place for generations upon generations of Native Americans. Both the early British and the early French explorers and fur trappers were introduced to the site by their native guides and trading customers. They took stories and specimens of these huge fossils back to their native countries, which ended up in the hands of leading naturalists and scientists who placed them in their cabinets of curiosities.

Eventually, these men of the Enlightenment compared and contrasted the knowledge and theories they'd gleaned from these unusual "new'" world specimens. Representatives of the North American contingent consisted of such folks as George Washington, George Rogers Clark, Ben Franklin, Charles Willson Peale and Thomas Jefferson. They were considered 'naturalists' and experts in this field of study.

But it was really Thomas Jefferson who got the ball rolling for us here in America. He was an instrumental champion for the exquisite natural history extant here in North America. He wrote only one book in his life, "Notes on the State of Virginia." Of course, what is now Kentucky was part of Virginia at that time (1781), and he made mention of the large bones found at Big Bone Lick. Jefferson believed that natural anomalies (wonders) needed to be studied and preserved. He personally purchased the tract of land in Virginia, which contained Virginia's Natural Bridge.

In 1779, while Governor of Virginia, he delivered a military grant of 1,000 acres (which included Big Bone Lick and its surrounds) to Colonel Christian, who in turn sold it to David Ross. Both of these men were friends of Jefferson, which meant he would retain access to this place that contained those strange, big bones. Therefore I like to think that it was Jefferson who first attempted to preserve this rare piece of real estate for the sake of scientific study and knowledge.

While Thomas Jefferson was President, he pulled off one of the most famous and spectacular land deals in history — pretty much right under the noses of Congress — when he acquired the 'other two-thirds' of our country from France. Then he planned, organized, coordinated and initiated his very own 'moon landing' for the time when he sent William Clark and Meriwether Lewis, with a handful of men (mostly recruited out of Kentucky, because Kentucky kicked ass even way back then), to explore that western territory and meet and interrogate the natives to learn about their cultures (even though many of them had never seen a white man before, much less understood his language).

Another of Jefferson's directives was to find out where those giant mammals, the mastodons, had finally settled. Remember, Jefferson at this time was not a believer in extinction. He was sure the beasts had simply relocated.

I think the most significant aspect of the Lewis and Clark Expedition was the fact that Thomas Jefferson had ordered Lewis (in 1803) to stop at Big Bone for a week on his way down river to meet up with Clark in Louisville, prior to heading out west. Then, after the explorers not only "landed on that moon" and extensively explored it and laid foundations for their 19th century "space stations," Jefferson had the gall to ask William Clark (in 1807) to also stop at Big Bone for some major specimen collecting on his way back home.

Here is a guy who just spent three or four brutal years in an unknown and uncharted wilderness, anxious to get back home to Louisville and finally marry his betrothed, and Jefferson convinces him to first spend several weeks digging up bones. That alone should demonstrate the importance of Big Bone Lick as a unique and valuable natural resource.

Rising interest in Big Bone Lick

The first organized attempt to establish an awareness-oriented citizen support group occurred on June 10, 1935, when a group of distinguished Kentuckians formed The Big Bone Lick Association. Three of them were known for their scholarly scientific literary achievements.

Willard Rouse Jillson was the Kentucky State Geologist for many years and a prolific writer of Kentucky history. He published "Big Bone Lick" in 1936, which remains the authoritative text on the subject. In 1928, W.D. Funkhouser was the co-author of "Ancient Life in Kentucky," along with William S. Webb (the father of Kentucky archaeology). Funkhouser was a professor of Zoology at the University of Kentucky, and Webb was a physics professor. Together they were the founding fathers of the Department of Anthropology and Archaeology at the University. Boone County's own John Uri Lloyd — scientist, novelist and eclectic medicine pharmacist — rounded out the group. The life of the Big Bone Lick Association was to be 99 years. Unfortunately, Jillson's book was the only major accomplishment to come from the organization.

In the early 1950s, a renewed interest in the significance and scientific importance of Big Bone Lick was fostered by several members of the newly formed Boone County Historical Society, which resulted in the formation of Big Bone Lick Historical Association. Their goal was to preserve this rare scientific site by raising funds to purchase it and turn it into a state park.

After many years of tireless efforts in promotion, education and fundraising, these determined individuals, through the leadership of Bruce Ferguson (future county Judge Executive and president of the organization) and William Fitzgerald (secretary), purchased 16 and 2/3 acres in December 1959, and presented the land to the Commonwealth of Kentucky for the purpose of making it a state park. Their thinking was that the state park system would preserve and promote the place's scientific importance and integrity. Boy, were they wrong! The next year, the Department of Parks announced its plans to develop picnic areas and a shelter house. Nothing even hinted at scientific study and research.

Back in 1979, I tried to promote a "Big Bones Come Home" event, as that date represented the 250th anniversary of the first big paleontological discovery in 1729 at Big Bone Lick by a French military expedition. Well, that was a French cartographic error — it was really 1739! — so I tried again in 1989 with absolutely no response or interest.

However I did convince then-Judge Executive Bruce Ferguson (remember, he was the president of the Big Bone Lick Historical Association back in the 1950s) to assist me in forming a non-profit 501c-3 group that we named Friends of Big Bone. I served as president for many years.

Finally I just could not take it any longer with the State of Kentucky and the Kentucky Parks Commission. After starting from scratch every four years when a new governor appointing a new Parks commissioner after each election, I gave up that ghost. As did several succeeding presidents of FOBB. That is until Patricia Fox took over the reins and recruited her team of board members and officers to stand their "scientific (back)ground" and persevere. God love 'em they are making headway.

My biggest beef, however is the fact that we have to sell rubber snakes and cupcakes in order to make money to promote and interpret true science whose 12,000 year-old evidence is here for the taking while, just 17 miles down the road, The Creation Museum receives funds to peddle a story that the Earth is only 6,000 years old and humans put saddles on dinosaurs and rode them to town!

All we want at Friends of Big Bone is a little Rodney Dangerfield-type respect. My dad always told me to avoid talking religion or politics in public, and I never had the knowledge or insight to argue, "But Dad, that's where the money is!"

Visit friendsofbigbone.org or the group's Facebook page for more information.

Head on over to the shop for great deals on fresh Kentucky gear, or come on down and visit us at the Fun Mall, y'all! 720 Bryan Ave. in Lexington.